As reported by the

Gainesville Times, Rick Lavender

Local News, August 06, 2006

To view the source site for this and more news articles on Micajah Clark Dyer, click here.

To view the source site for this and more news articles on Micajah Clark Dyer, click here.No one knows what convinced Micajah Clark Dyer Jr. he could fly more than a century ago. But many descendants of this Union County mountain man are convinced he did. In a boat-like craft built before "airplane" was a word and years before the

Wright brothers cleared a beach on North Carolina's Outer Banks.

The Dyer legend even made it to a road sign last month. State Rep. Charles Jenkins, D-Blairsville, sponsored a bill naming a stretch of Ga. 180 near Blairsville as

Micajah Clark Dyer Parkway.

"I think there's a lot of credibility to the story," Jenkins said.

Others will disagree. In the southern Union community of Choestoe, however, the 19th century "dirt" farmer some regard as a genius is a heavy favorite.

Sylvia Dyer Turnage, a great-great-granddaughter, and her husband own what was Dyer's farm at the foot of Rattlesnake Mountain. Dyer supposedly skidded down the steep mountainside on slicked wooden rails to take off.

Turnage recently showed two small models of his craft, made by a family member. Plastic green Army men filled in as pilots.

The account of at least one eyewitness, who has since died, and others passing along stories told as true about her great-great grandfather are reputable, Turnage said.

"That's why this story has stayed alive."

Ga. 180 leaves U.S. 129 north of Neel's Gap and south of Blairsville, crosses the Nottely River, and whips past pastures and creeks flanked by rumpled mountains. The Appalachian Trail treads these highlands. Brasstown Bald, Georgia's tallest peak, is a short drive up the two-lane highway.

Dyer's mother, Sallie Dyer, moved here with her son and parents from South Carolina in 1833. Micajah Clark Dyer Jr., born on July 23, 1822, was no older than 11. He may have been illegitimate, according to family researcher Ken Akins, noting that the boy's father didn't make the move and the child took the name of an uncle, Micajah Clark Dyer Sr.

Sallie remarried. But her son, called Clark to distinguish him from his uncle, was raised by his grandfather, according to a booklet Turnage wrote.

The new start in the Choestoe district came in a new county. Union had been carved in 1832 from Cherokee Indian territory. Choestoe is Cherokee for "Land of the Dancing Rabbit."

But life was no dance here. The mountains region was rugged and remote. Farmers scrounged a living in the valleys. Town meant Blairsville, the county seat incorporated in 1847.

Self-reliance was crucial. Neighbors could be scarce. As of 1848, Union's population numbered only about 5,800.

By then, Micajah Clark Dyer Jr. had married and fathered two children, with seven more to come. He also had begun studying the flight of buzzards and birds of prey, pondering a mystery that would fascinate him for life:

How to fly.

The

Gainesville Eagle announced in July 1875 that Dyer had received a patent for a "flying ship."

The short account went on to describe the craft and highlight the inventor's confidence that he had "solved the knotty problem of air navigation." But the article also said Dyer had studied the subject for 30 years and tried other experiments, all of them failed until now.

That work resulted in stories passed down for generations, settling into local lore like morning mist along a mountain stream.

Twenty years ago, Akins, Turnage's nephew, and a fellow college student began backtracking on the stories. Their work and that of others, including Turnage, reveal a relative out of kilter with any picture of a backwoods pioneer.

Akins said Dyer, of whom no photograph exists, had piped water to his log home at the head of Rough and Stink creeks. The gravity-fed system, a first for indoors plumbing in Union County, ran from a reservoir on the hillside above the home. Dyer later switched from hollowed-out logs to iron pipes.

Family members now dead also recalled a home with the logs hewn to a precise fit, a yard strewn with "gadgets and stuff," as Akins said, and a back workshop closed to all but a few and whispered about by neighbors.

In the workshop, Dyer supposedly created a perpetual motion machine, a Holy Grail for 19th century inventors. He even sent a model of it to Washington, D.C. According to family, his son Mancil inexplicably turned down a $30,000 offer for the invention after his father's death.

But Dyer was working on something else behind closed doors. A flying ship.

"The neighbors thought he was loco," Turnage said. "They couldn't understand why anybody at that time would spend such time on such a wild idea."

Dyer wasn't alone. The quest to create flying machines was growing worldwide.

An online database lists pages of U.S. patents involving aviation from 1799 through 1909. The age-old desire to fly was

shifting from balloon flights in the 1780s to the concept in the 1800s of a heavier-than-air, fixed-wing craft with a propulsion system and movable surfaces for control.

Peter Jakab, aeronautics division chairman at the

Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., said that by the 1870s, "Serious, established engineers ... were starting to take aeronautical investigation seriously."

That interest helped spur research papers, presentations and data sharing, building a mountain of trial, error and evidence that Wilbur and Orville Wright later used.

In addition to their creativity and organization, the Ohio brothers examined what others were doing.

"They had a great ability to assess the positive and dead-end patterns," Jakab said.

They also recognized that an airplane is a system of inventions, all vital, he said.

The Wrights are credited with building the first fully controllable glider in 1902. After adding a gas engine and propellers, Orville Wright recorded what is widely considered the first sustained, powered flight in a controllable heavier-than-air aircraft on Dec. 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, N.C.

Dyer had followed a different design to reach a similar end decades before, according to family.

Some who knew Dyer said he first built a scale model of the craft, adding a propeller turned by a clock spring. The model flew, they said.

Some people interviewed by Akins and Bob Davis also said the same of the larger aircraft.

Akins, now managing director at the state's

Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site in Cartersville, remembered talking with Johnny Wimpey, Dyer's grandson.

Wimpey, of Blairsville, was 8 when his grandfather died. He was nearing 100 and in frail health when Akins interviewed him.

Wimpey was sitting on a couch, his face blank, until Akins mentioned Dyer's flying machine.

"It was like he came to life," Akins said.

As a boy, Wimpey had helped Dyer build a rock wall, and Dyer often had allowed him into his workshed. Wimpey said he had seen the flying machine. He had even seen it in the air.

Dyer reportedly built rails up the side of Rattlesnake Mountain. He then slid the craft down them, picking up speed to take off into a cornfield just across Stink Creek.

"He said he actually flew it up that valley," Akins said.

Up, and back and forth, he said.

When Akins went to leave that day, Wimpey exclaimed, "I'm telling you the truth!"

"He kept saying that as I went out the door," Akins said.

Wimpey's account, the tales of others about Dyer's flights and the consistency of the stories made a believer out of Akins.

Yet, until about two years ago there was only anecdotal evidence.

Dyer had supposedly applied for a patent. But none could find it.

Then a younger relative tried the Internet search engine Google in 2004,

an unimaginable option when Akins and Dyer were scouring paper records in the 1980s. A link to the patent popped up.

Turnage heard about the find during church. She hurried home after the service and typed in a few key words.

"I saw the patent," she said. "All my life, I'd heard about the patent."

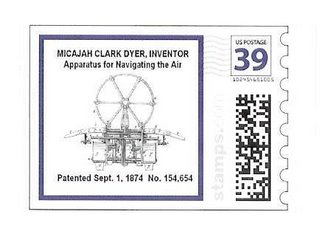

Patent No. 154,654, applied for in June 1874 and approved that Sept. 1, describes in technical writing and sketches Dyer's "Apparatus for Navigating the Air."

The so-called flying ship looks like a small boat under a tube-shaped balloon. There are three flap-like wings on each side. Dyer wrote that the craft can be run by steam or other power, in this case paddle wheels.

According to the 1875 Gainesville Eagle account, which was reprinted in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat and at least one other newspaper, the balloon lifted the ship. Dyer's patent description says the covering could be made off any strong, lightweight material that was waterproof and airproof. Akins said some suggested he used boiled corn husks.

The wings, or flaps, worked up and down together or individually, and could be angled for altitude, according to Dyer.

A rudder helped steer the creation.

The details and scope seem startling for a man who may never have gone to school or read much more than the family

Bible. He certainly wasn't privy to the aviation schemes circulating in engineering circles.

"The drawing is so precise," said Jenkins, an aerospace retiree from the former Lockheed Corp., "I would say somebody from Georgia Tech couldn't do better."

The details didn't necessarily fit popular ideas of what Dyer might have made. Those leaned toward a fixed-wing craft.

But the patent did match stories told by those who knew him or his children. Accounts including pedals and a body built of white pine.

The patent also helped lead to the road-name change, celebrated in a

May 31 signing with Gov. Sonny Perdue at the Capitol and a

July 15 dedication coinciding with a family reunion at Choestoe Baptist Church.

Turnage acknowledges that she has been captivated by the stories for years. She even wrote a poem, since put to music, telling of Dyer's invention rising from the earth, "a sight to behold indeed."

It also is hard to find longtime residents in Choestoe who don't know the story and don't have some tie to the Dyer family. Most believe that Micajah Clark Dyer Jr. actually flew.

Roma Sue Turner Collins said her grandmother, a Dyer, saw the craft airborne.

"I would just put my life on it that it's a true story," Collins said recently.

Jakab might disagree. The aviation expert from the Air and Space Museum saw only a rough sketch of the invention this week. By those dimensions, which roughly mirror the drawings in the patent, he said the balloon does not appear large enough to lift the craft.

The flappers, as opposed to fixed wings, also were "one of the great barriers" to advancements in flight, because the physics don't work for heavier-than-air aircraft, Jakab said.

Dyer's design appears instead more in the line of a lighter-than-air craft, because it apparently depends on a balloon to stay aloft, and possibly as a dirigible or steerable balloon.

Whether that stance will float with Dyer descendants is questionable. But there's another pressing question: What happened to the invention?

Dyer died at age 68 in the winter of 1891. He continued to work on his airship until his death. The Gainesville Eagle story suggests that as of 1875 he had not built the patented version of it. But he planned to, and according to the family's research, did.

After Dyer's death, the word is that his widow, Morena, sold the aircraft to two Redwine brothers from Atlanta or Gainesville. Akins writes that she may have needed the money.

The tale then is that the Redwines possibly sold the craft to the Wright brothers.

The latter connection is open to speculation. The Wrights, said Jakab, seem to turn up rightly or not in almost every story involving the history of early flight.

But believers in Dyer's accomplishments will continue to dig. The family is hoping someone will build a full-scale version following the patent. There also is talk of including Dyer in a 2007 exhibit at the

Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins.

Turnage recently walked visitors past Stink Creek, where Dyer had a grist mill, and into what is now a hayfield where, as the story goes, he took to the air. Turnage's home is near where Dyer's once stood, overlooking the field.

On this hazy summer day, a plane buzzed high over the green mountains. Turnage said someone once commented, "We flew over your place,"

"I told him, 'Don't you think you're the first guy to do it.'"

She hopes to one day learn what happened to her great-great-grandfather's aircraft, and whether there's any truth to the Wright brothers story. But Turnage, like Akins, considers one mystery settled.

Asked if she has any doubts that Dyer flew, she answered smiling but firmly, "Oh, no."

Contact:

rlavender@gainesvilletimes.com, (770) 718-3411.

Back to Top

Back to Top  Home

Home

Back to Top

Back to Top  Home

Home

According to legend, the family and neighbors actually saw him navigate the craft over his fields. He reportedly applied for a patent for the machine, and it was believed that after his death in 1891 his widow sold both the contraption and the plans to some brothers named Redwine. The family still firmly believes that those items eventually wound up in the hands of the Wright brothers, who were credited with making the first manned flight in 1903.

According to legend, the family and neighbors actually saw him navigate the craft over his fields. He reportedly applied for a patent for the machine, and it was believed that after his death in 1891 his widow sold both the contraption and the plans to some brothers named Redwine. The family still firmly believes that those items eventually wound up in the hands of the Wright brothers, who were credited with making the first manned flight in 1903.